|

ERNIE LE BRUN KATHLEEN CHANTER MURRAY THOMPSON ROSE LE BRUN |

|||

|

Name: Murray Thompson

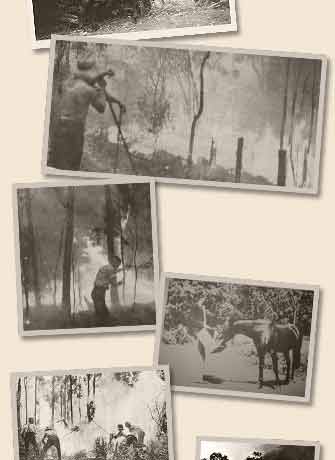

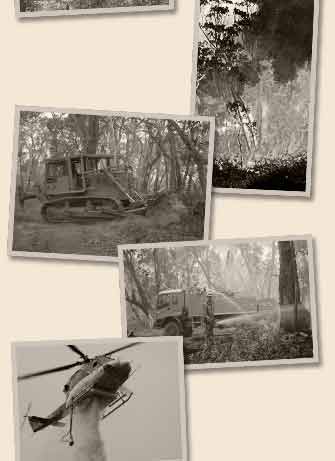

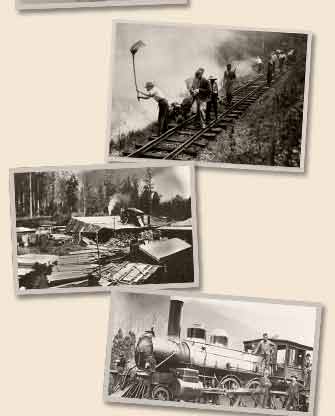

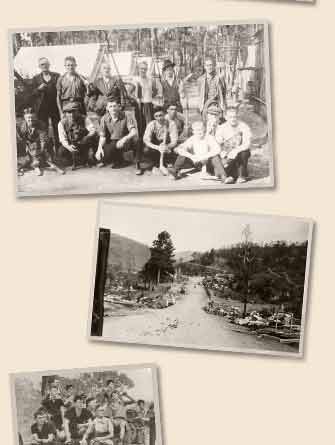

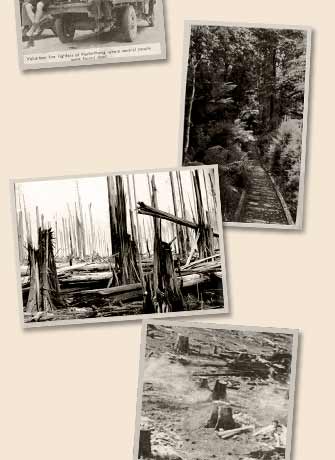

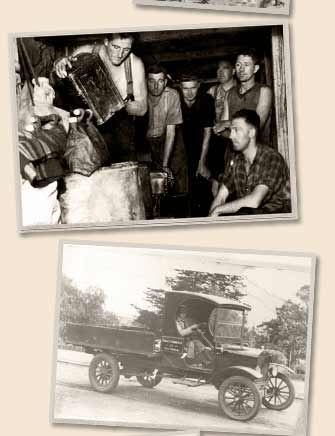

Age: 88 Occupation during 1939: Working for the Forestry Commission at Narbethong, branding and checking the logs in the mills. Age at time of fire: 24 Location of interview: Ballarat "You worked all through the night, because that was the coolest part. You slept in the heat of the day, when the fire was going like hell, because then you couldn’t do anything about it." I was 24 when the fire came through Narbethong, and that was on the Sunday morning. I’d been playing tennis. It was quite a mild day, with a south-west wind blowing, and the fires were the last thing I was thinking about ‘til lunchtime. That’s when forester Frank Burns, in charge of the pine plantation at Narbethong, rang up to say there was a fire in the plantation and would I come along to see it. So I saddled up my pony, and I had a parcel of sandwiches down the front of my shirt, with a bottle of cold tea. And I had two nails in my pocket, and hooked onto my saddle was a head of a rake, because when I got to the fire, somebody would cut a handle for me out of a small tree and I could nail it on. I also put a bit of bran and oats and stuff for a feed for the pony. And me and my horse and my rake, we went off to fight the 1939 fires. Rather comical when you –think about it. I saw a little fire a little while ago on the telly where there was a bulldozer, a grader, 11 tankers and helicopters, coming to fight a little scrub fire that we normally would have put out with about 20 men. The things I remember about the 1939 fires are factors which influenced it, like the manpower we had at the time. We had forestry employees, we had sawmill staff, fallers and mill hands, and we had bushfire brigade men - they were volunteers, but they were very great-hearted men. And the causes of fires, there were many. Lightening, sawmills, steam engines - we’d get sparks from all of those. Gold miners, they liked to burn everything off the ground so they could find gold. Graziers, camp fires that had been neglected, and tourists. And then there was travelling stock and people clearing land on the edge of the forest. Now the tools we had to fight the fires were rakes, slashers, cross-cut saws, and knapsack pumps, axes and shovels. None of the gear you’ve got today. The transport available were horses, bicycles, motorbikes and utilities. Tankers were extremely rare and in the grass country only. Communications were nil, and water supplies were not very well developed. There were a few dams, and you were lucky if there was a local creek handy. We used to have a couple of 44-gallon drums of water on the back of a ute, but they could have been parked up a couple of miles away. The population was very small, and the access to the forest was very limited, maybe non-existent. And what there was would be steep, rough, boggy in places, or animal tracks. It was generally hard to get in there, and when there was a lot of smoke around, it was pretty hard to get out again. The solution, if the fire got too bad, was to stop on the burned ground until the weather abated. That could be quite a long time. The food supplies were whatever you could carry with you, like tinned peaches or potatoes in your pocket, and a canvas water bag. You didn’t sleep in the bush at night, you worked all through the night fighting the fire because that was the coolest part. It was in the heat of the day, when the fire was going like hell - that was when you slept, because you couldn’t do anything about it. "Their camp was in a green wet gully, and didn’t get burned. If they’d have stopped home, they’d have been safe. That was very sad." Can you visualise the top of the range, and the wind is coming from the south-west, and then it takes a turn north? Now, the fire was burning in the dry top of the ridge, and the top of the fire had gone well past us and we were just working on the flank of it on Sunday. Now on Monday, that fire, after it left us on Sunday, it went right across to the Rubicon about another 20 miles, and that’s where it pulled up for the night. Well, then it was very quiet on Monday, but Tuesday afternoon, after a quiet morning, the wind suddenly swung into the north-west and we had this fearsome, hot north-west wind. The north wind got behind that 30-mile front, and that was when the fun and games began. The fire really roared to life on Tuesday afternoon. It roared right up the Acheron Way and killed the Kerslakes and burnt all the mills. That’s when the first lot of the damage was done. Well, then the fire was away from us. We couldn’t do anything. See, we couldn’t travel, we couldn’t go anywhere. We just stopped where we were, and cleaned up a bit around houses. There weren’t many houses, for that matter. Wednesday and Thursday were both quiet, and then the north wind came up again on the Friday. That’s when shocking damage was done, but I wasn’t in that, I was at the back of the fire. I got a taste of it on Sunday and on Tuesday afternoon, and then my next job was as a member of the rescue party who found the Kerslakes family and those Greek men on the Acheron Way - which was devastating. Where the Kerslakes were, there was the car and Ken and the Greek, and then a little bit further on was his wife, and Ruth the little girl. She was just lying in the middle of the road. We thought she was asleep. But she had her dad's tobacco in one hand, and some money in the other hand, and she was sort of running back. She must have died of asphyxiation, because she certainly wasn’t burned or damaged. That was very tragic, because if they’d stopped in Narbethong when they’d got there in the morning, they’d have been right. And ironically, at their camp, which was in a green wet gully, it didn’t get burned. If they’d have stopped home, they’d have been safe; if they’d have stopped where they were in the morning, they’d have been safe. So that was very sad. I couldn’t believe the ferocity of that fire in ‘39. At the start of the Acheron Way where it left the highway, there was a neglected sawmill there. A.E. Hermon’s, its name was, and they had a big clearing there with just stumps of big trees and a few saplings. I often used to ride past there and think to myself, now if ever there was a fire in this country, this is where I’d make for, because it’s a nice big clearing, and it should be pretty safe. But I changed my mind very smartly when I saw what happened there after the 1939 fires. The tree stumps were hard, big. You can imagine a stump about four feet in diameter, solid wood and about waist high? That’s where they cut the log from, and there were saplings growing through. Well, when we came back with the rescue teams, we could see there must have been a fire storm there. "A little bit further on was his wife, and Ruth the little girl. She was just lying in the middle of the road. We thought she was asleep. She must have died of asphyxiation." Now, a fire storm as I understand it, and as I’ve seen it, is when a fire is burning so furiously with this awful wind behind it, that all the eucalyptus gas in the leaves of the gum trees is burning, which creates these big balls of flammable gas coming in front of the fire. And there is not enough oxygen in the air to burn it. But when you get to an open paddock, and the fire and the wind behind it eases a bit, this big gas ball - almost like a full gasometer - gets enough oxygen from the air in the clearing. A spark then gets in it, and it just blows up like an atomic bomb. That is what happened in this nice clean space of Herman’s mill that I thought was going to be so safe. Every small gum tree had completely disappeared and the stumps - instead of being four foot in diameter and three foot high - they were about one foot in diameter and about two foot high. Now, you could just imagine the violence and the ferocity of the fire that hit those stumps, that burned four or five feet of solid green wood off a stump with no logs, no nothing, no kindling or anything - they just disappeared. "The Acheron river dried up and didn’t run for about three hours. It’s incomprehensible, the violence of it. That’s what stopped the Kerslakes and the Greek men." As we went up the Acheron Way, the fire was on about a half-mile front, apparently, because there was a strip about a half a mile wide where the great big ash trees, which were 200 or 250 feet tall, were screwed off. Just like you’d screw a match in half, about 60 feet up. Where they were still between three or four feet of solid wood, they were just screwed off, and 60-foot stumps were left there and the heads were on the ground. And I can speak of that with authority because Feiglins had sawmills and fallers salvaging these stumps. And I had the job of measuring them and branding them so that they could be taken to the sawmill and sawed up. I know that belt of devastation went for at least 14 miles up the Acheron Way, and fellers I knew reckoned the same thing went all the way to Matlock. That same terrible devastation went all that way. Teddy Taylor, he was the mill foreman, he told me that the Acheron river actually dried up and didn’t run for about three hours, and then it started flowing again. It’s incomprehensible, just the violence of it, and that’s what stopped the Kerslakes and the Greek men. "The trauma and physical exhaustion took such a toll that when I arrived home in Melbourne, it took my own mother some time to recognise me." The trauma and physical exhaustion caused by the fire took such a toll, that when I arrived home in Melbourne several days later, it took my own mother some time to recognise me. In those days of course, there was no such thing as post-trauma counselling. We did get a week with paid holiday though. After the fires, when Judge Stretton’s Royal Commission came to Narbethong, to the best of my remembrance, he was at the school. I gave testimony at the Royal Commission. I worked for the forest commission for 39 years, and with the three years at the forestry school, 42 years of my life has been associated with the forest commission. I have been retired since 1975 with a national medal recognising ‘35 years of diligent service’. |

|

||

|